Press Review

Film review for the Brasov Alpin Film Festival

(Original article from Ioana Clara Enescu article in Romanian)

Stories worth telling

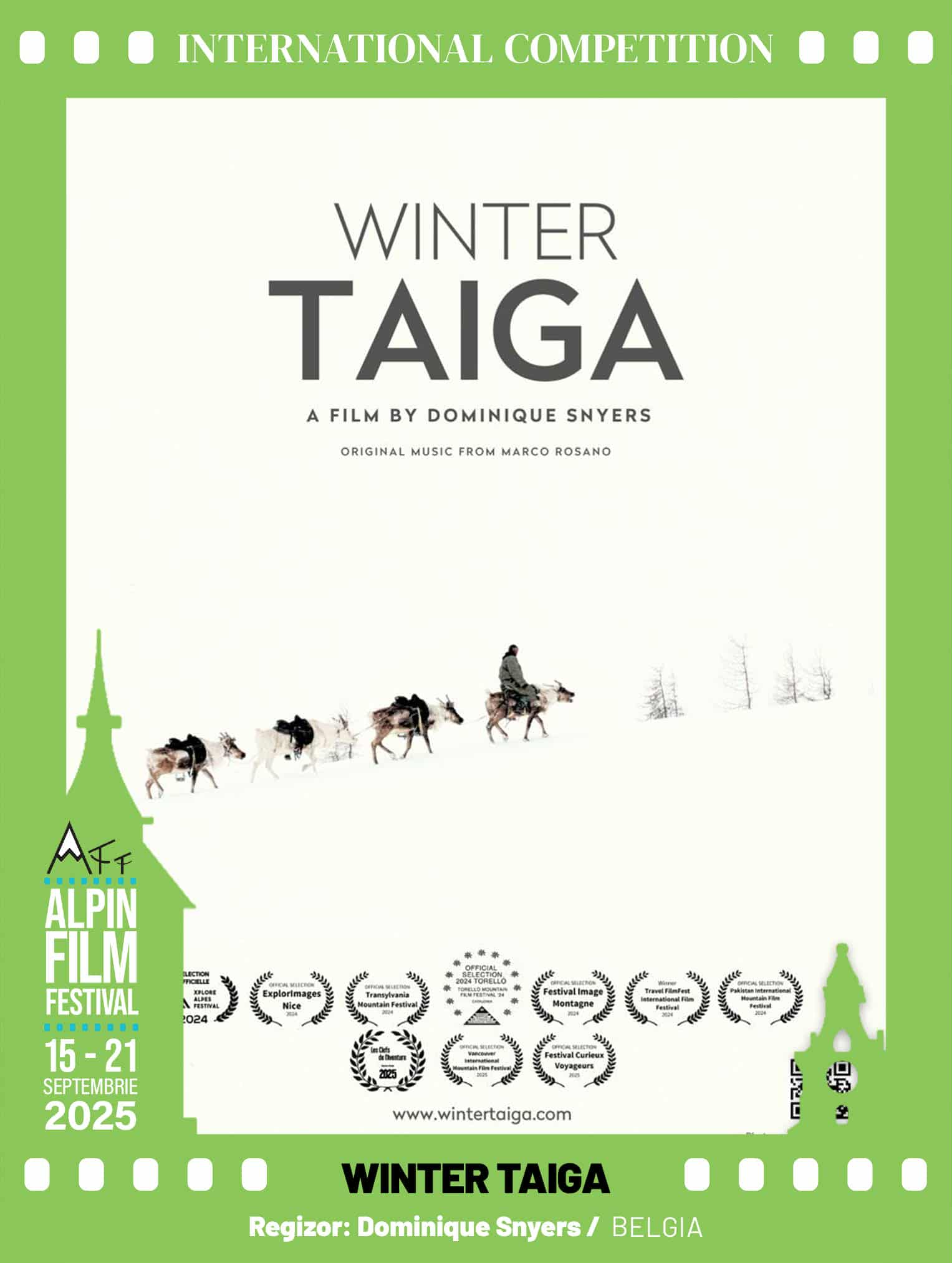

A frozen, unreal blue needle, broken by white lines, seems to me like an inverted sky on which you can see the trails left by shooting stars. The camera angle makes the sled, which has a few people on it, appear to be flying among the galaxies as it slides on the surface. I pause the trailer and replay the sequence a few times. Each time, I see the lake as a sky on which stars dance, with a sled floating through it as if pulled by Santa Claus’s reindeer. From the comfort of my room in front of my laptop, it’s easy to find poetry in pixels, but I know I wouldn’t if I were in that sled in winter on Lake Khovsgol, northern Mongolia. This is the introduction to the film Winter Taiga (Belgium–Mongolia, 2024, dir. Dominique Snyers), presented at the Alpin Film Festival (2025). It seduces the viewer with images that have been carefully selected by a director who admits to having always been fascinated by vast spaces and enthusiastic people.

As in any true documentary, the beauty of the image in Snyers’ film is not an end in itself, but a means of making the viewer aware of the world they are about to discover. In this world, Lake Khovsgol is not just any body of water, but the freshwater heart of Mongolia — a sacred place with cold, clear waters that turn into an ice road in winter. For the local people, Lake Baikal’s younger sister is not just a visual spectacle, but a source of water and food — an essential part of the web of life. The terrible frosts in winter and the dizzyingly hot summers are extreme conditions for Europeans living in a temperate continental climate.

For the reindeer herders who feature in the documentary, however, these conditions are part of everyday life. People, plants and animals have all adapted to the large temperature fluctuations, the endless expanses and the limited resources. The documentary captures life in the taiga over 12 days in winter, as seen through the eyes of a family of reindeer herders and Western visitors.

The documentary focuses on the symbiotic relationship between humans and reindeer: humans protect and care for the reindeer, who in turn provide them with mobility and food. Despite their small stature, reindeer are resilient and strong, and people admire them for this. They love freedom and are docile, says one of the herders. In another scene, we hear him calling out to his herd in a language they understand immediately. One night, wolves attack the reindeer, providing visitors with an opportunity to learn that in the taiga, irreconcilable oppositions do not exist; rather, there is an understanding that all forms of life have the right to exist. When one of the herders says that wolves are more worthy of pity because they do not have a whole herd at their disposal like humans do, it becomes clear that the few nomads who still cross the Taiga with their reindeer have a relationship with the world that the modern world has forgotten.

Filming in winter amplifies both the technical difficulties and the visual impact. Sometimes, the only indication of the horizon line is the presence of people and reindeer, appearing as small black dots in the distance. General shots of seemingly monotonous white expanses reveal upon closer inspection to be webs of shadows, traces and lines that slowly fill the space like reindeer walking through loose snow. The viewer’s gaze is forced to become attentive and distinguish subtle differences; to be patient like the taiga’s inhabitants, who measure every step. Close-ups linger on faces that are sometimes harsh and sometimes deep in thought; on steamy reindeer breath; on large, gentle eyes; on a bloody reindeer leg after a wolf attack; and on smoke floating in the tent like a forest spirit.

Meanwhile, in the background, the film draws attention to Mongolia’s dilemma: the choice between preserving traditional rural life and the allure of modern comfort. The episode in which the youngest son of a reindeer herder expresses his dream of opening a karaoke bar through a drawing is emblematic of an entire generation. However, the epilogue reveals that, for the time being at least, he has chosen to remain in the taiga, start a family, and care for the reindeer. This choice is not final though, suggesting that people oscillate between continuity and change.

Winter Taiga is more than just a visually stunning film in which the Mongolian winter plays a central role. It is also an invitation to look around you more carefully so that you do not miss the stories of compassion, grace, and resilience that deserve to be told.